Escape from Alcatraz

Don Siegel has made a prison film that strips away the melodrama and gets down to business. Working with Clint Eastwood in their fifth and final collaboration, he’s crafted a movie that respects both its audience’s intelligence and its source material—J. Campbell Bruce’s account of the 1962 breakout from America’s most infamous prison.

What’s remarkable about Escape from Alcatraz is how it functions as both a throwback to classic prison pictures and something entirely modern. Siegel and screenwriter Richard Tuggle invoke the familiar archetypes—the brutal warden, the philosophical lifer, the sadistic guards—yet avoid the sentimental pitfalls that usually accompany them. There’s no forced romance, no contrived backstory explaining why we should root for these criminals. Instead, the film operates on a more primal level: the fundamental human drive for freedom.

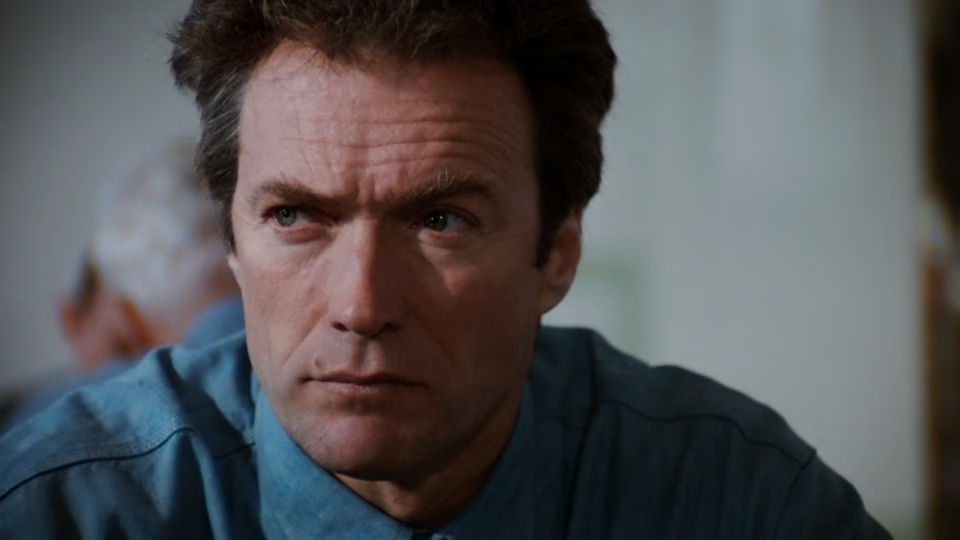

Eastwood, now approaching 50, remains a commanding screen presence. His Frank Morris is introduced in a nearly wordless opening sequence that follows his arrival at Alcatraz with documentary-like precision. We watch him processed like livestock and marched naked to his cell. Eastwood’s weathered face and muscular frame tell us everything we need to know about a man who’s spent his life behind bars. This is the Eastwood persona distilled to its stoic, resourceful, unbroken essence.

The genius of Siegel’s approach becomes clear as the film progresses. Rather than focusing on why Morris wants to escape (the answer is obvious), he’s fascinated by how. The final act becomes an extended sequence of pure visual storytelling, following the escape attempt in real time with minimal dialogue. Bruce Surtees’ cinematography captures the darkness of night without sacrificing clarity, creating an atmosphere where every shadow could hide discovery.

The film’s refusal to provide easy answers extends to its ending. We never learn definitively whether Morris and his companions survived their swim to freedom, and Siegel wisely resists the temptation to provide closure. The ambiguity isn’t a cop-out but a recognition that sometimes the attempt matters more than the outcome.

Tuggle’s script, while economical with words, finds moments of dark humor. When a guard comments on Morris’s sudden interest in Bible study, unaware that the book conceals his digging tool, Morris replies with characteristic dryness: “It’s opening up all kinds of new doors.”

The technical execution throughout is exemplary. Filming on location at Alcatraz itself lends authenticity that no studio set could match, and Siegel uses the prison’s imposing architecture to create a sense of claustrophobia that makes the eventual escape feel genuinely liberating.

But it’s Siegel’s final visual joke that elevates the material. As the credits roll over Morris’s papier-mâché decoy head, we see that he’s painted a broad grin on its face—his final message to the authorities who would discover it. Whether Morris lived or died, he got the last laugh. In that single image, Siegel captures something essential about the American spirit: the refusal to be caged, even in the face of impossible odds.

Escape from Alcatraz works because it trusts its story and its star. In an era of increasingly loud and complicated films, Siegel has made something admirably direct—a movie about men who refuse to accept their circumstances and the ingenuity required to change them.