The Birthday Party

Director William Friedkin’s third feature adapts Harold Pinter’s play described as “a comedy of menace.” Spoilers follow.

The story follows disheveled and unemployed Stanley, the lone tenant in a dingy boarding house in an English seaside town. The house’s owners view him as something of an adopted son, though he proves prone to mood swings and ramblings and seethes with angst. One day, two men named Goldberg and McCann arrive. They claim to want to board, but Stanley suspects something more sinister.

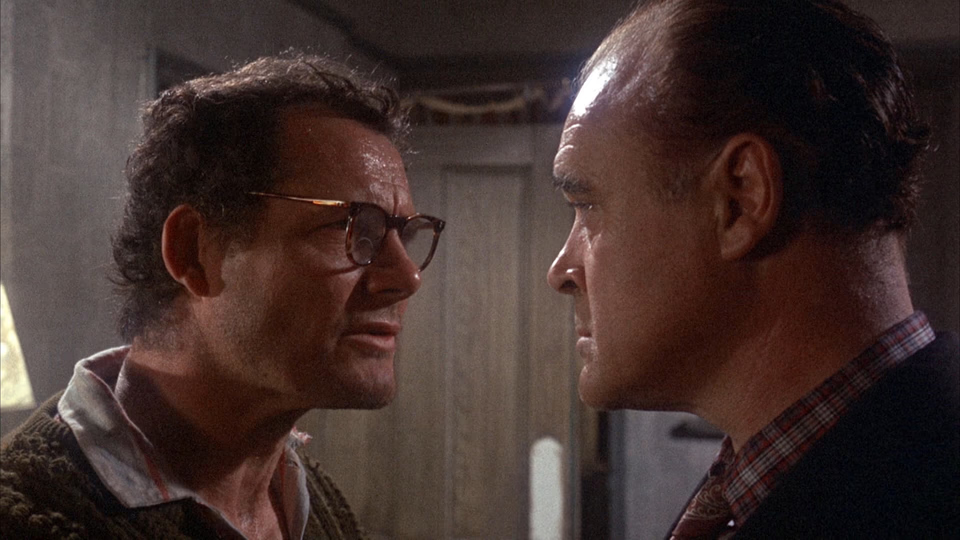

Indeed, their motives are sinister, though unclear. They plan to throw Stanley a birthday party, though Stanley insists it’s not his birthday. Prior to the festivities, they interrogate Stanley, pushing him to the brink of madness. By party’s end, they break him.

The next morning, a clean-shaven, well-dressed Stanley emerges from his room with Goldberg and McCann. Unable to form words, Stanley alternates between pained squeaks and mute silence. He leaves with Goldberg and McCann.

As with his prior productions, the road to Friedkin directing The Birthday Party proved circuitous. He chronicles it in his autobiography, The Friedkin Connection.

He first saw Pinter’s play in 1962 in San Francisco. It was his first trip outside Chicago, made possible by his debut documentary, The People vs. Paul Crump, which was competing in the San Francisco Film Festival. It won the festival’s highest award. The next morning, Friedkin saw ad advertisement for The Birthday Party, describing it as “a comedy of menace.” He saw it that night. Despite the thrills of the festival win, the play proved more pivotal and resonant.1

Fast-forward to 1968. Fledgling company Palomar Pictures was trying to make low-budget films with young directors who wouldn’t cost or spend a lot of money. Friedkin proposed adapting The Birthday Party, filming in London on one set for a budget of $1 million or less. Palomar reached a deal with Pinter, contingent on the playwright’s acceptance of Friedkin.2

Wrote Friedkin, “I was warned that he tended to be intimidating, but I found him engaging, accessible, courteous, and modest. He was taller and more muscular than I had expected, with black curly hair and dark, penetrating eyes.”3

Having worked with Sonny Bono on his debut, Good Times, Friedkin had experience managing large egos, and was aware of his position. He wrote, “I must have seemed as strange to Harold as his plays did to many theatergoers. I was young but with no interesting film credits, no theater experience, no impressive education, and I was American to boot. I had little to recommend me except Fantozzi’s assurances to Harold’s agent that I was a brilliant director. I had two mediocre films, one of which was yet to be released, and an episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. Harold’s fame was spreading. He had shifted the paradigm of what was possible in serious drama, blurred the line between truth and falsehood in his characters. “Pinteresque” had entered the language to mean something challenging or difficult to decipher. I had the financial backing to make the film but Harold didn’t need money.”4

But unlike Good Times, this production built upon a solid foundation in Pinter’s play. Pinter himself adapted the script, and Friedkin loved it, writing, “I had no desire to clarify what he had purposely kept ambiguous. I relished the pauses and the silences that conveyed dramatic effect as much as the language.”5

And unlike Friedkin’s prior production, The Night They Raided Minsky’s, he got a first-choice cast. Robert Shaw convinces as tortured Stanley. Patrick Magee menaces as ape-like heavy McCann. Sydney Tafler flips between congenial charm and sinister menace with unsettling ease as Goldberg.

But it’s Dandy Nichols who surprises, disappearing into her role as the lonely middle-aged boarding house owner that grounds the film. A fearless performance given her character’s unflattering lighting and grating dialog. It’s the contrast between her verisimilitude and McCann and Goldberg’s absurdity that heightens the film’s sense of dread.

These choices came via Pinter, not Friedkin, who admits, “Left on my own, I wouldn’t have known to cast any of them, but to this day I don’t think our cast could have been improved.”6

Friedkin leverages innovative camera-work to liven the single-room setting, including POV shots, a bird’s-eye view, and a dynamic device whenever the lights go out. Wrote Friedkin, “When the lights were out, I went from color to black-and-white. As the blindfolded characters moved about the room, I had a camera attached to a gyroscopic mount on their backs pointing over their shoulders on a wide-angle lens as they shuffled around in darkness.”7

But Friedkin never allows his formal technique to overshadow the source material. “My staging was designed to keep the actors moving as much as possible and let the camera follow them. If a scene called for them to remain static, I would slowly and imperceptibly move the camera closer or pull away. I tried to keep the camera invisible, but there were times when I couldn’t resist and opted for radical angles,” he wrote.8

Indeed, for the first time in his feature career, Friedkin had a film he believed in, writing, “In the end I made the film I wanted to make. Palomar released it without fanfare in a handful of theaters, and it didn’t find an audience. I had hoped the film would bring redemption for Good Times and Minsky’s. That wasn’t to be. But The Birthday Party is a film of which I’m proud.”9

Friedkin and Pinter evoke a nightmarish atmosphere with allusions to paranoia, authoritarianism, and conformance, but the oblique nature blunts its impact. Wrote Friedkin, “The play can be viewed as a metaphor for the police state, society’s need to make the individual conform, the need of the strong to dominate the weak, the futility of resistance, the tyranny of religious persecution, and our inability to empathize with the suffering of others. It’s all of this and more, but it’s best enjoyed for its surface pleasures, a disturbing comedy-drama about irrational fear and paranoia. It’s not that Pinter’s characters can’t communicate—they communicate only too well, even though they use language to conceal their true feelings.”10

To that end, your mileage will depend on your appetite for Pinter’s obtuse style. While I appreciated the absurdist elements, I wished it committed to them. Instead it pulls back, almost too British to surrender. The result leaves the film with something of an identity crisis between a genuine commentary on forced conformity and an ironic satire. Pinter seems aware, as evidenced by Stanley, full of menace, asking his host, “Tell me, Mrs Boles, when you address yourself to me, do you ever ask yourself who exactly you are talking to?”

Notes

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 54, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 122, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 122, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 123, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 126, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 126, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 131, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 131, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 132, Kindle. ↩︎

-

William Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection (HarperCollins, New York, 2013), 125, Kindle. ↩︎