Dutchman

Dutchman is a film that writhes with tension but never quite breaks free of its stage origins. Adapted from Amiri Baraka’s provocative play, this 55-minute psychological thriller unfolds entirely within the confines of a sweltering New York subway car, where a chance encounter between a young black man and a seductive white woman becomes an unsettling dance of desire, power, and racial politics.

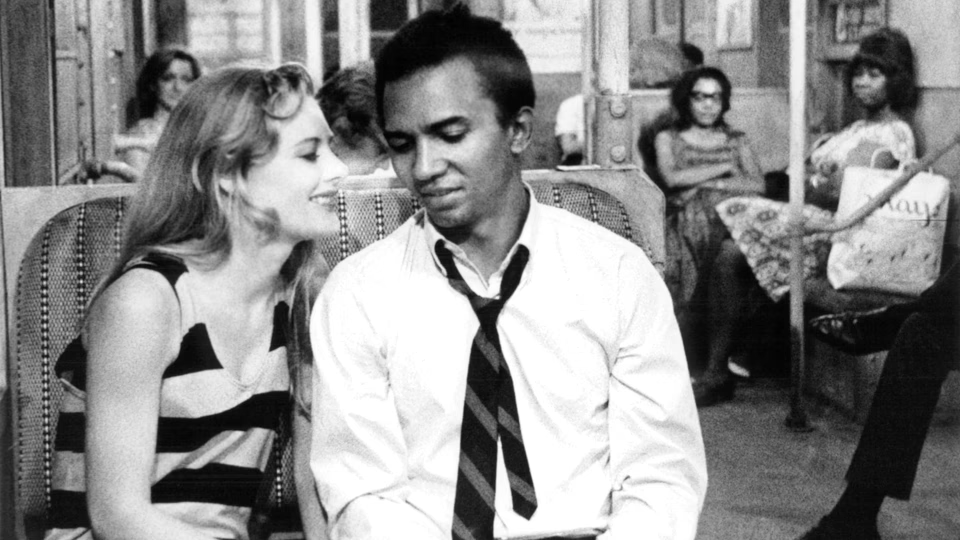

The film opens promisingly enough, with a sinuous John Barry score (fresh from his James Bond compositions) accompanying our introduction to Clay (Al Freeman Jr.), a reserved, well-dressed black man riding alone. Enter Lulu (Shirley Knight), a blonde temptress who might have wandered in from a Tennessee Williams play. What follows is a pas de deux of provocation, as Lulu cycles through various personas—seductress, ingénue, racist tormentor—in her attempts to crack Clay’s carefully maintained facade.

Director Anthony Harvey, making his debut after editing for Stanley Kubrick, demonstrates a sharp eye for composition and rhythm. His dynamic editing amplifies the claustrophobic setting, turning this simple subway car into a pressure cooker of racial and sexual tension. Yet for all his technical prowess, Harvey can’t quite solve the fundamental challenge of opening up this material for the screen.

The biggest hurdle is the theatrical nature of the performances. Knight, in particular, while capable of projecting both allure and menace, plays to the back row when the camera begs for subtlety. Her Lulu transforms from enigmatic presence to apparent mental patient so rapidly that it strains credibility when Clay doesn’t flee at the next stop. Freeman fares somewhat better, but both actors are trapped delivering monologues that feel more like position papers than organic dialogue.

The film’s allegorical ambitions are both intriguing and frustrating. Biblical imagery abounds—Lulu munching apples and offering them to Clay like a subway Eve—and the script hints at supernatural undertones that suggest Lulu might be some eternal predator of young black men. Or perhaps Clay is the true monster for his reluctance to confront the racism that surrounds him. These are provocative ideas, but they’re delivered as meandering rants instead of cogent insights.

At least the film’s brevity works in its favor. At 55 minutes, it doesn’t overstay its welcome, making it accessible to viewers interested in this slice of ’60s racial commentary. But those seeking a more nuanced exploration of similar themes would do better to watch George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, which manages to be both more subtle and more devastating in its racial allegory.

Still, Dutchman remains an interesting artifact of its era, a film that captures the burning racial tensions of the 1960s through a lens that’s part psychological thriller, part supernatural allegory. But like the subway car in which it’s set, it feels like a vehicle that never quite reaches its destination.