Who Can Kill a Child?

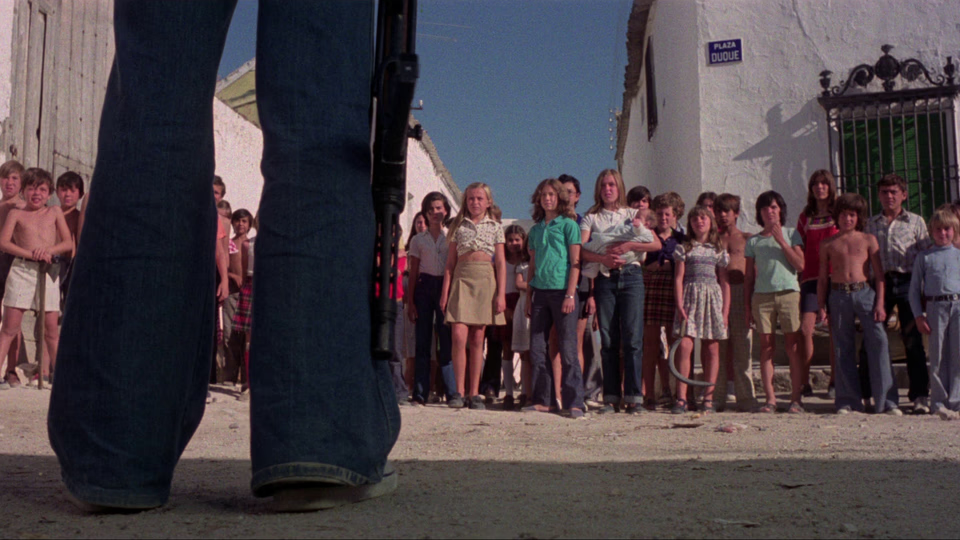

The Spanish island looks like a postcard. White adobe walls. Brilliant sunshine. Nobody home except the kids.

That should be your first clue to get back in the boat.

Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s horror film starts strong with atmosphere you can taste. The opening mainland sequences burst with life—festival crowds, fireworks, bodies packed so tight on the beach you can’t see sand. Then comes the island: empty, silent, suffocating despite the open air. The white walls pop against the heat. The sweat glistens. Serrador knows how to frame dread.

But he doesn’t trust it.

The film opens with nearly ten minutes of documentary footage—Holocaust horrors, Vietnam carnage, dead children. Later, a shopkeeper intones, “It’s always the children who suffer the most.” Message received. And received again. And again. What could have been an eerie, ambiguous nightmare becomes a thesis statement with body counts.

The setup works. English tourists Tom and his pregnant wife Evelyn arrive at a remote Spanish island to find it devoid of adults, and the children acting strange.

They find a café with burned chickens still rotating, half-eaten meals on tables. Tom’s theory? Everyone’s at a “festival” on the other side of the island.

Then a little girl beats an old man to death with a stick. Tom carries the body deeper into the village—not away from danger, deeper into it—so Serrador can stage a scene where the kids string up the corpse like a piñata and hack at it with a scythe. A gruesome callback to the mainland festivities, but also contrived.

Lewis Fiander tries his best as Tom, though his gangly run undercuts the terror. When he leaves Evelyn alone to search a boarding house for—police? backup? Serrador’s blessing?—any remaining sympathy evaporates.

The film insists we’d all refuse to harm children. Maybe the villagers who knew these kids by name. But tourists being hunted with knives? Please. When Tom finally shoots one, the film treats it like a moral collapse. I thought, “What took you so long?” Evelyn’s hysterical response feels like another contrivance to keep them from escaping.

There’s a lean, mean thriller buried here under ten pounds of allegory and forced stupidity. Tom throws away weapons. Evelyn goes hysterical at precisely the wrong moments. They have the self-preservation instincts of lemmings.

The inexplicable island menace of nature (or children) turning against us evokes Hitchcock’s The Birds, but where Hitchcock trusted mystery, Serrador over-explains. The children “infect” others through proximity. The eerie score telegraphs every supernatural moment. By the end, needless exposition drains whatever power remains.

Horror works best when it whispers. This one shouts.

The craftsmanship shines. The concept disturbs. But Serrador won’t get out of his own way. He’s so busy making sure we understand his point that he forgets to make us believe his people.

The island is beautiful. The children are terrifying. The script needed another draft.