Naked Lunch

David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch isn’t really an adaptation of William S. Burroughs’s 1959 novel. It’s a fever dream that stitches together that book, other Burroughs stories, and the writer’s own tragic life into something that probably won’t make much sense unless you’ve done your homework.

Peter Weller plays William Lee, a Burroughs stand-in working as an exterminator in 1953 New York. His wife Joan has been shooting up his bug poison for a “literary high.” Lee hallucinates a giant talking beetle that recruits him as a secret agent and orders him to kill Joan. He does kill her—accidentally, during an inebriated William Tell routine where he shoots at a glass on her head and misses.

Then Lee flees to Interzone, a North African hellscape that may exist only in his drug-addled mind. There he becomes hooked on “black meat,” a narcotic harvested from giant centipedes. He writes “reports” on a talking insect typewriter. The typewriter gives him assignments. He seduces his dead wife’s doppelgänger and one of the “Interzone Boys” named Kiki. The whole secret agent plot is nonsense, a MacGuffin. What Cronenberg is really after is the connection between addiction, art, and self-destruction.

The finale makes this clear. When asked to prove he’s a writer, Lee kills Joan’s double in another William Tell accident. Cronenberg is making explicit what Burroughs himself believed: that his accidental murder of his real wife Joan in Mexico was what made him a writer. Art requires sacrifice. Sometimes unconscionable sacrifice.

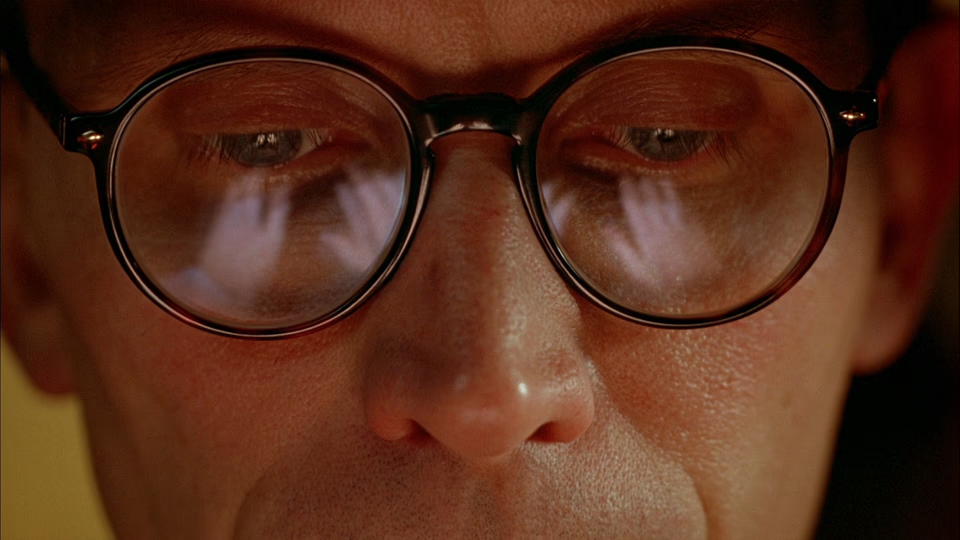

Weller moves through this nightmare landscape with his trademark opacity. It’s the same blank affect that made him perfect for RoboCop, and here it works brilliantly. He never reacts to the grotesqueries around him—the bugs with talking anuses, the alien creatures ejaculating narcotics—which somehow makes them more disturbing. We’re trapped in Lee’s head without a guide to tell us how to feel.

Cronenberg does the impossible. He makes Burroughs’s unfilmable prose squirm on screen without ever feeling cheap or exploitative. The body horror maestro is in his element, crafting images that repel and fascinate in equal measure.

What emerges is a portrait of genius as self-annihilation. Lee doesn’t just suffer for his art. He destroys everything around him, fueled by guilt and desperate narcosis. It’s fascinating. It’s nihilistic. It’s deeply uncomfortable.

This is an easy movie to admire and a hard one to enjoy. I’ve watched it three times across three decades, and only now does it click. Maybe that says something about the film. Maybe it says something about me. Either way, it demands that you meet it on its own terms. Come prepared with knowledge of Burroughs’s life and work, or don’t come at all.