And God Said to Cain...

There’s something to be said for a director who understands that atmosphere can carry a film where plot cannot. Antonio Margheriti’s And God Said to Cain arrives with the threadbare revenge premise we’ve seen countless times before, yet Margheriti transforms this familiar material into something approaching the sublime through sheer visual audacity.

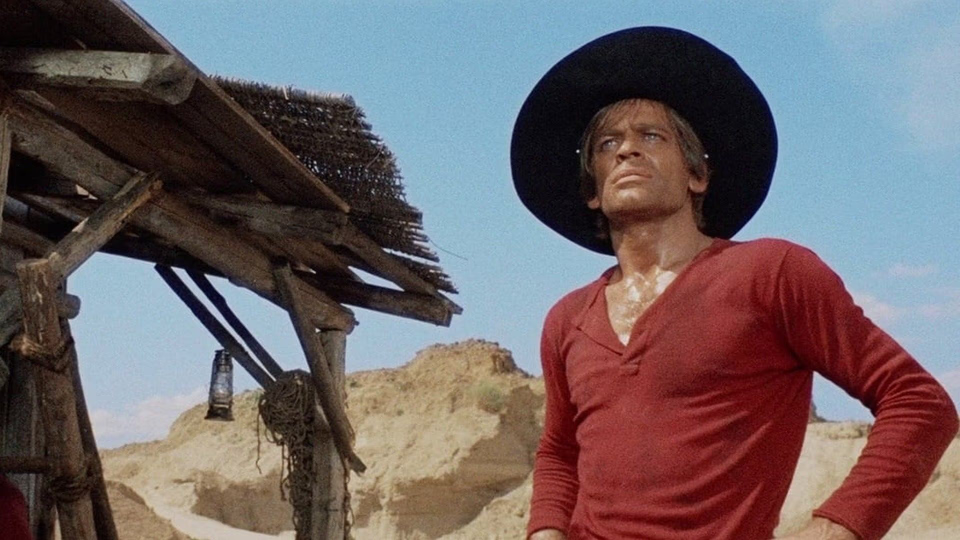

Klaus Kinski, that master of the unnerving stare, plays a Union soldier freed after ten years in a brutal work camp, returning to his hometown with vengeance on his mind. The setup is pure western boilerplate—betrayed by friends, framed by lovers, now back for payback. What makes this picture worth watching is how Margheriti turns a conventional revenge tale into something resembling a gothic horror film that happens to be set in the American West.

Kinski is perfectly cast here, his gaunt frame and those piercing blue eyes suggesting a man hollowed out by suffering and filled with purpose. It’s unfortunate that he’s dubbed in both the International and Italian versions, robbing us of that distinctive voice that could add even more menace to the proceedings. Still, Kinski’s physical presence carries considerable weight—he moves through the film like a specter, emerging from shadows and underground passages with the inevitability of death itself.

This is where Margheriti’s direction truly shines. Rather than staging straightforward gunfights in dusty streets, he transforms the town into a maze of shadows and hidden passages. His camera finds unusual angles, his lighting creates stark contrasts between light and dark, and his production design—particularly in those interior scenes—would make Hammer Films proud. When Kinski times his arrival with a fierce storm, Margheriti doesn’t simply turn on a wind machine; he fills the air with straw and dust, making the very atmosphere feel hostile and alive.

The film functions less as a traditional revenge western and more as what we might now recognize as a proto-slasher film. Kinski uses a network of underground catacombs to move unseen through town, picking off his targets one by one in increasingly inventive ways. There’s a particularly memorable death involving a church bell that demonstrates both Margheriti’s visual flair and his willingness to embrace the macabre.

The director also stages some genuinely thrilling action sequences, including a standout moment where a wounded man, vastly outnumbered, throws open a corral gate. Storm-spooked horses come thundering out directly toward the camera, trampling his adversaries in a visceral display of practical filmmaking that puts many modern effects to shame.

Yet for all its atmospheric pleasures, And God Said to Cain suffers from feeling like the third act of a longer, more complete story. We never witness the original betrayal that sets everything in motion, nor do we see Kinski’s character seethe and wait for his mission of vengeance. As a result, when former friends meet their fates, we feel little of the vicarious satisfaction that drives the best revenge narratives. The deaths register as well-crafted set pieces rather than emotionally satisfying payoffs.

This structural problem keeps the film from achieving true greatness, but it doesn’t diminish Margheriti’s considerable formal achievements. His visual approach elevates every scene, finding poetry in violence and beauty in decay. Combined with Kinski’s magnetic screen presence—even when dubbed—and topped off with a surprisingly catchy theme song, And God Said to Cain becomes a fascinating curio that demonstrates how style, when deployed with sufficient conviction, can transform even the most familiar material into something memorable.

The film may not reinvent the revenge western, but it certainly redecorates it with enough gothic flair to make the familiar feel fresh again.